Pro Se Litigation

WHY THIS CASE MATTERS

It's not about the money. It's about the metadata.

I initially filed this lawsuit to recover unpaid wages. But while preparing for Discovery, I uncovered something far more dangerous than a payroll error: Forensic evidence suggesting that Corporate Managers can rig internal investigations without oversight.

When I found the server logs showing that my investigation was "concluded" at 11:14 AM—while witness interviews were still scheduled for that afternoon and the following day—the mission changed. This indicates the verdict was predetermined; they finalized the report before hearing all the evidence.

I am not fighting this battle to hurt my former employer. I am fighting to ensure that Insurance Carriers and Corporate Boards implement the necessary audits to stop this from happening again.

Pro Se Litigation - Adventuring Alone

From time to time, individuals might find themselves navigating pro se litigation - not because they planned to, but because certain situations leave no alternative. Sometimes the issue starts with what appear to be bad actors. You don’t know whether they’re acting alone, whether management would support them if exposed, or whether the entire structure above them would double down and behave even worse once confronted.

Unfortunately, situations like this do occur. And now, at over 50 years old, I’ve found myself in a position where it’s me—alone—against a large organization. Despite repeated warnings about their conduct, their actions have only escalated the situation.

Below is the first detailed case study in this journey: The importance of Digital Forensics.

Winning with the Physical Facts Rule: Why Forensic Data Trumps Testimony

By Christopher Daniel

The 11:14 AM Anomaly:

In the modern American legal system, justice is often a function of resources. Large corporations, armed with "white shoe" law firms and unlimited budgets, effectively own the narrative. They can bury an individual plaintiff in procedural motion practice until the litigant runs out of money, energy, or hope. In this traditional script, the "facts" are determined not by what actually happened, but by which side can produce the most managers willing to align their testimony.

But in the case of Daniel v. Envirotest Systems Corp (Case No. 2025CV243), currently pending in Colorado’s Larimer County District Court, that script is being rewritten by a server log.

Strategies for Winning Pro Se Litigation Against Coporations

Overcoming The "David vs. Goliath" Dynamic

The disparity in this case could not be starker. Envirotest Systems Corp (dba - Air Care Colorado), a subsidiary of a global vehicle inspection giant, is represented by Littler Mendelson, P.C.—widely recognized as the largest employment law defense firm in the world. Their business model is built on defending management decisions and insulating corporations from liability.

Across the aisle stands Christopher Daniel, a former IT Administrator and insurance claims investigator acting as his own attorney (Pro Se). Without a legal team or a war chest, Daniel has turned to a different kind of counsel: Immutable Digital Forensics. Leveraging 16 years of experience in data analysis, he has mounted a case based not on subjective arguments, but on the "Physical Facts Rule"—a legal doctrine stating that oral testimony which contradicts undisputed physical facts (like physics, timestamps, or GPS data) must be disregarded.

"Witnesses can be coached," Daniel notes in his filings. "Timestamps cannot."

Exposing Administrative Fraud and Falsified Records in Discovery

Pillar 1: The 11:14 AM "Smoking Gun" and Pre-Determined Outcomes

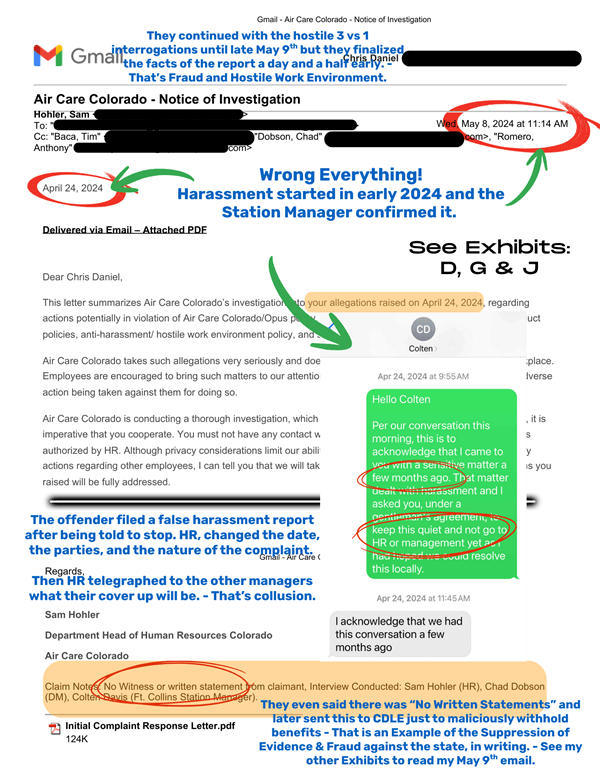

The heart of the lawsuit exposes what Daniel alleges is a "rigged" internal investigation designed to legitimize a predetermined outcome. The centerpiece of this allegation is Exhibit D, a "Notice of Investigation" generated by Envirotest’s internal HR system.

Forensic metadata contained in the case file proves that this official record was created and timestamped at 11:14 AM on May 8, 2024. This document purports to be the record of the investigation into employee complaints. However, the timeline of physical events contradicts the digital record.

According to court filings, the actual investigation—the process of interviewing witnesses and gathering facts—had barely commenced when this file was generated. Daniel alleges he was subjected to a grueling series of four separate "3-vs-1" interrogation-style interviews, occurring over the course of two days (May 8th and May 9th).

These interrogation sessions were not standard HR interviews; they were hostile confrontations involving multiple managers, including Anthony Romero, the direct supervisor of the very person Daniel had complained about. This presence created an immediate and unaddressed Conflict of Interest.

"It is a forensic impossibility for the investigation to be valid," Daniel argues. "The system generated the official record at 11:14 AM on May 8th. Yet, the interrogations didn't conclude until late the following day. The company effectively decided the outcome, finalized the record, and then went through the motions of interviewing me."

The Image Above: This is just an image over an image, with text and color overlap. It is not the actual exhibits which are on the docket as unredacted and unedited files. For display purposes, this image saves from requiring 2 more + the explanations for each.

The "Smoking Gun" of Prior Knowledge (Exhibit J)

Defense attorneys frequently argue that employee complaints are "recent fabrications" created solely to avoid discipline. Exhibit J dismantles that defense entirely.

On April 24, 2024—two weeks before the "Sham Investigation" was launched—Daniel sent a text message to Station Manager Colten Davis to memorialize a verbal conversation they had held months prior. In this text, Daniel explicitly confirms:

"I came to you with a sensitive matter a few months ago. That matter dealt with harassment and I asked you... to keep this quiet... as I had hoped we could resolve this locally."

Crucially, the Station Manager did not deny this. Instead, he replied at 11:45 AM, confirming the timeline of the company's knowledge: "I acknowledge that we had this conversation a few months ago."

The Falsified State Record This creates a fatal contradiction for the Defense. When Envirotest submitted their mandatory administrative report to the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE), they scrubbed this April conversation entirely. Forensic analysis of the CDLE submission alleges that HR altered the official Date of Incident, changed the Nature of the Complaint, and switched the Complaint Parties listed on the form.

The lawsuit argues that by manipulating these specific data points, the Corporation allegedly presented a sanitized narrative to the State—one where the conflict was a "sudden, new event" justifying termination, rather than a long-standing liability they had negligently ignored. Exhibit J is offered as proof that the State was misled.

Exposing Administrative Fraud and Falsified Records

Pillar 2: Suppression of Evidence

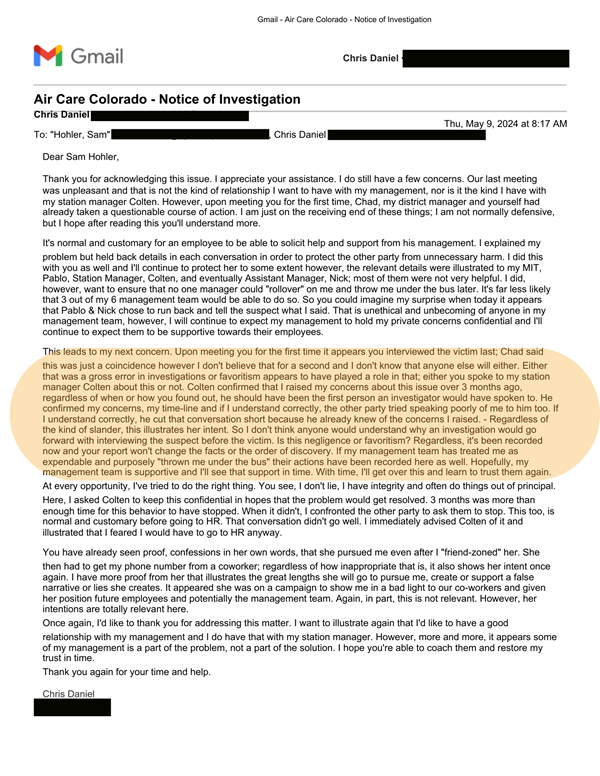

The lawsuit further alleges that this pattern of "curating the truth" extended to the corporation's dealings with the government. When the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE) began its inquiry into Daniel's termination, Envirotest was required to submit the administrative record.

In their official submission, the corporation claimed that the claimant "provided no written statement" regarding the dispute. This claim, if accepted, would paint Daniel as an uncooperative employee who failed to participate in the process.

However, Daniel has produced Exhibit G , an email server receipt that directly impeaches this claim. The receipt proves that a detailed, written statement was delivered to HR Manager Sam Hohler at 8:17 AM on May 9, 2024.

In that suppressed statement, Daniel explicitly questioned the integrity of the investigation while it was happening:

"Is this negligence or favoritism? Regardless, it's been recorded now and your report won't change the facts... It appears some of my management is a part of the problem, not a part of the solution." — Exhibit G (Email to HR Manager)

"They told the State of Colorado the document didn't exist," Daniel says. "My 'Sent' folder proves it does. This isn't a difference of opinion or a clerical error; it is a verifiable suppression of the record intended to hide the timeline discrepancies from state regulators."

Whistleblower Retaliation and the Negligent Retention of Malicious Agents

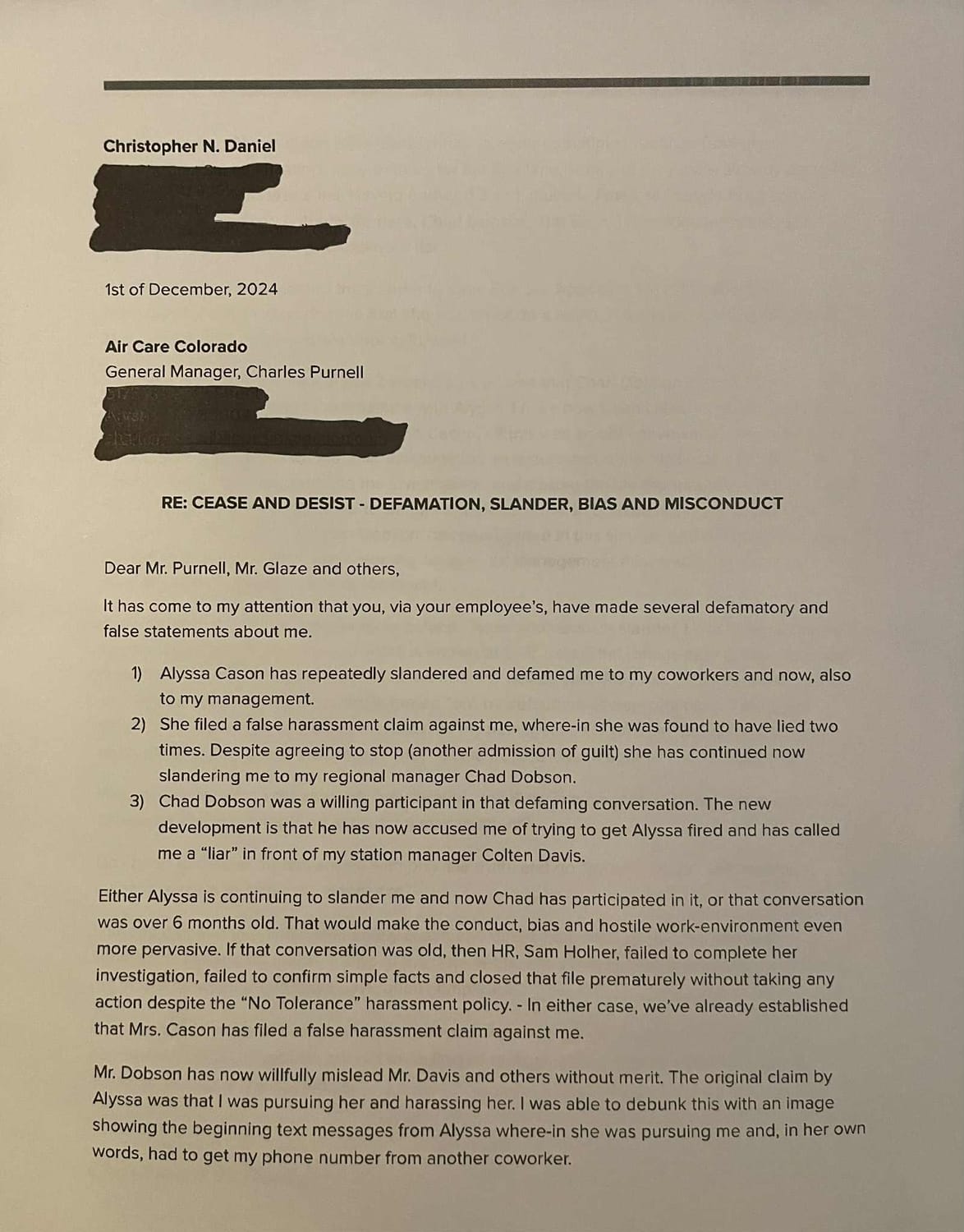

Pillar 3: Leveraging Cease & Desist Notice for Legal Standing

Perhaps the most damaging evidence for the Defense is the "Countdown to Termination." Retaliation cases often turn on the timeline: did the employee engage in "protected activity" (complaining about illegal acts), and did the employer fire them shortly after?

In Daniel v. Envirotest, the timeline is precise and documented by two separate exhibits that show a rapid escalation from legal warning to "nuclear" retaliation.

Step 1: The Denial of Mediation & Legal Warning (Dec 1 - Exhibit K, I & L) Before the termination, Daniel attempted to de-escalate the situation. He formally requested mediation to resolve the interpersonal conflict professionally. Corporate HR denied this request with silence.

This denial exposed a critical contradiction: While Envirotest maintains a written "Zero Tolerance" Harassment Policy, the Plaintiff alleges this policy is merely performative—selectively enforced against whistleblowers while actual harassment is ignored.

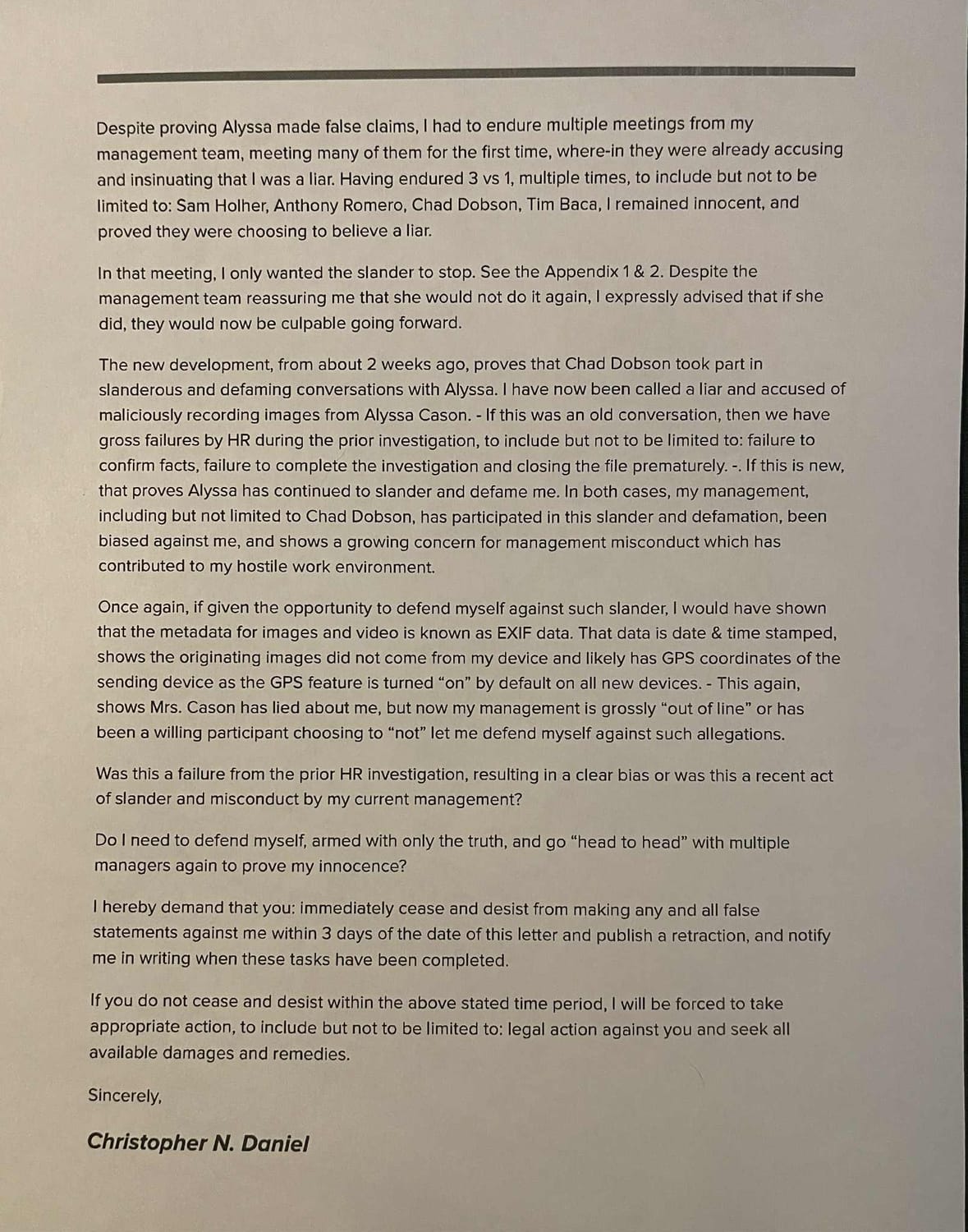

Left with no other option, Daniel served a formal "Cease & Desist" letter to General Manager Charles Purnell on December 1, 2024.

This was not a standard grievance; it was a specific legal notice alleging Negligent Retention. The letter placed management on notice of a toxic pattern—one the Plaintiff alleges amounts to the accuser making sport of targeting male hires while management looks the other way.

The "Ratification" of Misconduct:

"If that conversation was old... then HR failed to complete her investigation, failed to confirm simple facts and closed that file prematurely without taking any action." — Exhibit I

By denying mediation and ignoring the warning about the accuser's history, the Plaintiff alleges Management effectively ratified the hostile environment by answering the C&D with Silence.

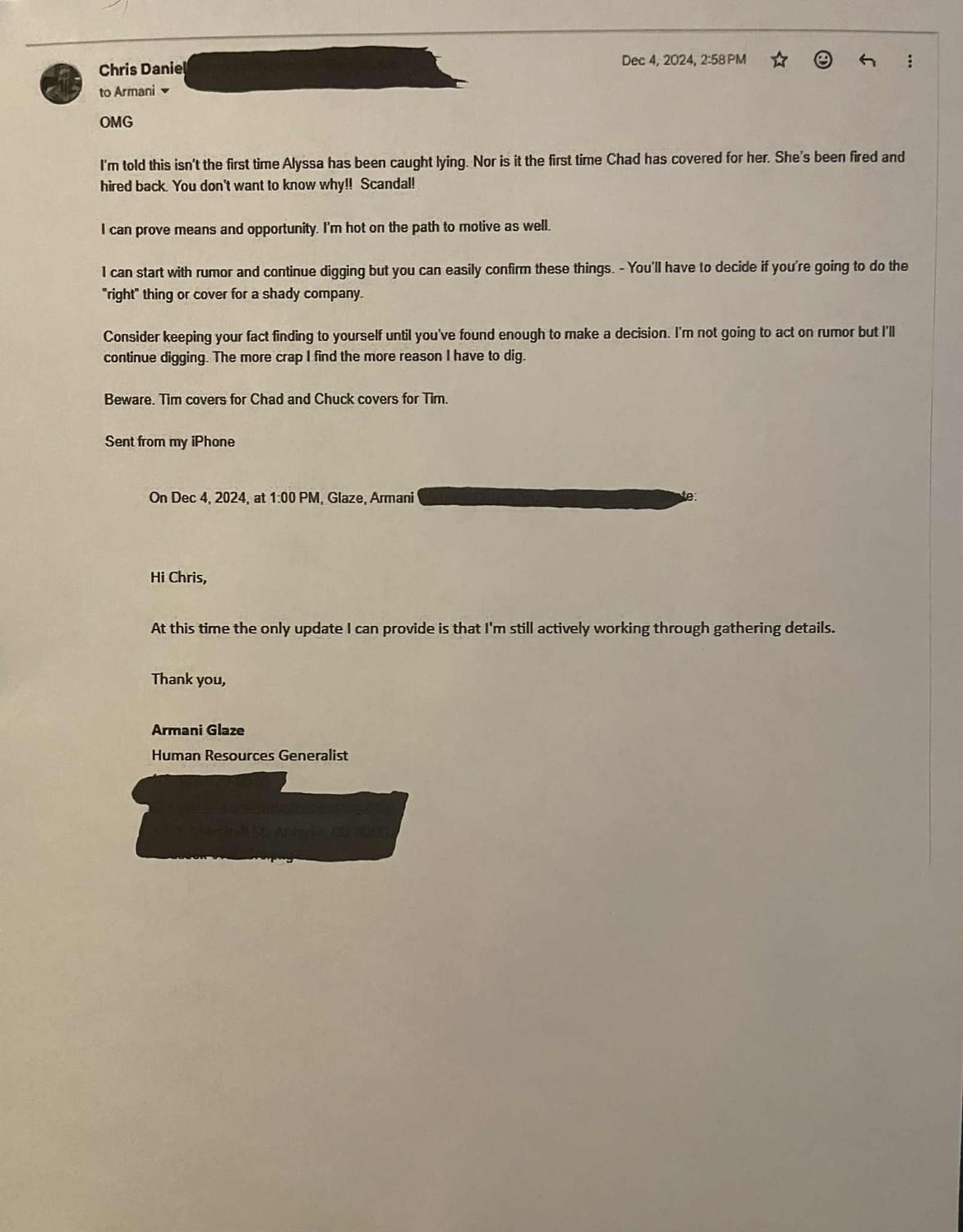

Step 2: The "Whistleblower" Ultimatum (Dec 4 - Exhibit L) On December 4, 2024, the conflict shifted from a personnel dispute to a corporate liability. Daniel sent a specific Whistleblower Report to HR Director Armani Glaze.

In this communication, Daniel did not ask for help; he issued a challenge. He stripped away the corporate pleasantries and explicitly identified the "Chain of Command" corruption that was insulating the bad actors. By naming the specific managers involved in the cover-up, he removed HR's ability to claim ignorance.

The Removal of Plausible Deniability:

"You’ll have to decide if you’re going to do the 'right' thing or cover for a shady company... Beware. Tim covers for Chad and Chuck covers for Tim." — Exhibit L

This email was the turning point. It forced the Corporation to make a binary choice: investigate the specific managers named (Tim, Chad, Chuck) or eliminate the employee who named them.

Step 3: The Termination (Dec 9) Exactly 120 hours after sending the "Shady Company" email—and just eight days after the Cease & Desist—Daniel was terminated.

"I went from having a 4.75/5-star performance review to being fired in five days," Daniel notes. "The only thing that changed in those five days was my report to HR exposing the chain of command."

When the State Agrees with You - Why You Still Have to Fight the Big Companies

Pillar 4: State Validation

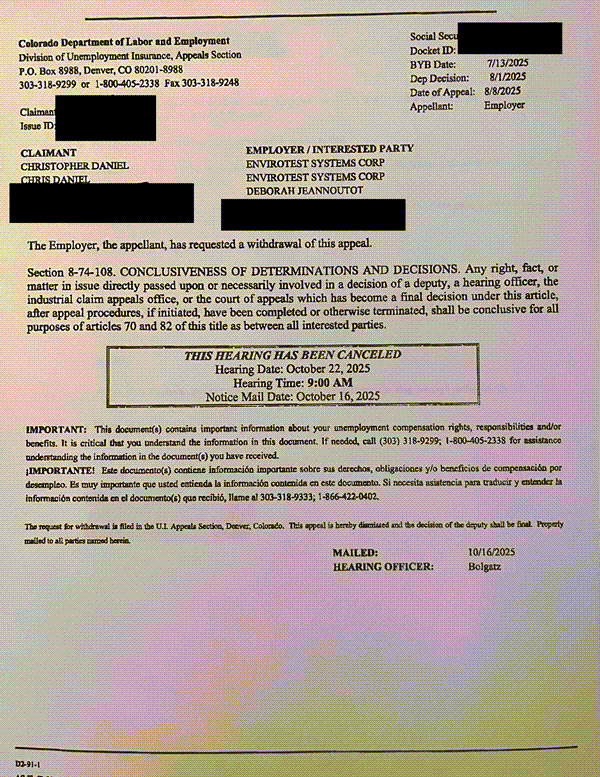

The State of Colorado has already weighed in on the legitimacy of the termination. The Colorado Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE) reviewed the facts and ruled that the employer failed to meet the burden of proof, potentially awarding unemployment benefits to Daniel.

Envirotest initially attempted to appeal this decision, likely realizing that a state finding of "No Just Cause" would be catastrophic for their defense in civil court. However, on October 16, 2025, the corporation abruptly withdrew its own appeal (Exhibit H), finalizing the state's finding .

"The Employer, the appellant, has requested a withdrawal of this appeal... This appeal is hereby dismissed and the decision of the deputy shall be final." — Exhibit M (CDLE Order of Dismissal)

By withdrawing, Envirotest effectively surrendered the argument, allowing the Deputy's decision—that the discharge was not for "Just Cause"—to stand as the final word of the state agency.

Furthermore, despite effectively conceding the state appeal, the lawsuit alleges that Envirotest has refused to correct Daniel's internal personnel file. By maintaining a 'For Cause' termination status in direct contradiction to the State's 'No Fault' ruling, the Plaintiff argues the corporation is engaging in continued defamation. This specific scarring has made it difficult to secure new employment, rendering the ongoing defamation particularly harmful and resulting in compounding economic damages.

The Clean Hands Doctrine

The Doctrine of Clean Hands: Why Transparency Matters "In the American legal system, a party seeking justice must come to the court with 'Clean Hands.' This means acting with integrity, honesty, and transparency.

Throughout this litigation, the Plaintiff has prioritized the Physical Facts Rule, providing the Court and the public with direct access to forensic server logs and metadata. In contrast, there are allegedly several accounts of documented Bad Faith, some involving Fraud and Malice, raise a significant question: Can a corporation that relies on falsified records and litigation delays claim to have 'Clean Hands' before the Court?

The alleged documented pattern of administrative fraud raises significant questions regarding the integrity of the data being supplied to the State of Colorado. As these facts are now part of the public judicial record in Case No. 2025CV243, the Plaintiff is evaluating the forensic impact this has on the current litigation and the 'Clean Hands' doctrine. The following forensic exhibits illustrate these specific allegations:

Bad Faith Examples

Multiple Indicators of Malice This exhibit provides a documented Employer Fraud Example (the 11:14 AM timestamp) and an Employer Bad Faith Example (the suppression of the May 9th written statement). By analyzing the server logs against the corporate narrative, the "Physical Facts Rule" identifies the specific points where the administrative record was altered to manufacture a "For Cause" termination. See Exhibits: D, G & J.

Insurance carriers routinely disclaim coverage for acts of intentional fraud and malice. When defense firms ratify these actions, it elevates their risk.

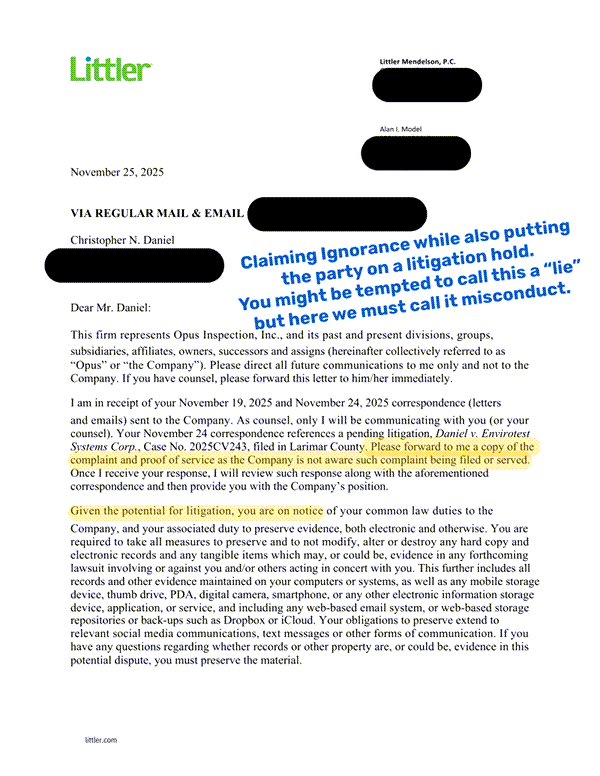

Litigation Misconduct Example: The 27-Minute Metadata Contradiction

This case study provides a documented Litigation Misconduct Example and evidence of Defense Counsel Bad Faith in Case No. 2025CV243. In Exhibit A, counsel asserts they are "not aware" of the lawsuit, yet the same correspondence issues a formal "Litigation Hold"—an action that only occurs when a party is fully aware of active litigation. Then, 27 minutes later, they tried to take advantage of a Pro Se again by making misleading statements via email.

This was just the beginning for them...

Utilizing the "Physical Facts Rule," this audit exposes the metadata contradiction used to delay discovery and serves as an instructional resource for identifying attorney misconduct and administrative inconsistencies.

INSTRUCTIONAL DISCLAIMER: The annotations in this case study represent the Plaintiff's formal legal allegations in Case No. 2025CV243. These public records are hosted for educational purposes to demonstrate the application of digital forensics and the 'Physical Facts Rule' in employment litigation.

No final judicial determination has been made.

Running Account of Alleged Bad Behavior So Far...

#

The Event / Act

The Alleged Legal Charge

1

Alyssa Cason's

False Claim

Alleged Fabrication of Evidence with Actual Malice - Manufacturing a "harassment" claim to flip the narrative on the whistleblower. Exhibit D, G, J

2

"Triple Fraud"

May 2024

Alleged Account 1 of Fraud with Actual Malice - Falsifying the date, parties and narrative to manufacture a "For Cause" firing. Exhibit D

3

Suppression of Evidence

May 2024

Alleged Bad Faith & Fraud with Actual Malice - Administrative Fraud & Suppression of Evidence with Actual Malice. Exhibit G

4

Nov. 2024

"Liar" Slander

Alleged Defamation Per Se - Chad Dobson attacking Daniel's professional integrity. Exhibit K, I & E (the EXIF metadata)

5

Nov. 2024

"48 Hour Sham"

Alleged Administrative Fraud with Actual Malice - Armani Glaze (HR) closing the "thorough investigation" in 48 hours while ignoring EXIF data. - Exhibit H & E

6

Purnell's

"Knowledge of Fraud"

Alleged Executive Ratification - GM Purnell by allowing the alleged fraud to continue after the Cease & Desist. This is now Systemic Corporate Malice. Exhibit I - Part 2 the email

7

The "Lane Speech"

Dec. 9th, 2024

Alleged Public Slander with Actual Malice - Manager Dobson characterizing Daniel as a "ruckus" to the crew. Pending RFA verification under Rule 36 or conclusive admission through default.

8

"Triple Fraud"

Aug. 2025

Alleged Account 2 of Fraud with Actual Malice - Submitting the same falsified report to the CDLE after receiving the Cease & Desist letter. Exhibit D x2 = Sustained Malice

9

27 minute Litigation Contradiction

Procedural Contradiction - From the initial contact, the Defense Counsel has been demonstrably misleading. Exhibit A

10

The Conflict of Interest raised from the ROR

The Reservation of Rights letter (Exhibit B) - Knowing there are at least a few managers who have willful & wanton acts of malice, the Defense has now ratified their conduct by electing to dual represent them & the company. These acts are Disclaimed by insurance.

11

The Procedural Admission and anticipate potential default

Consciousness of Guilt - Staying silent when faced with "Physical Facts" is a strategic choice to avoid the consequences of their previous bad behavior. I actually anticipate "word salad" as they have been "litigating the clock instead of the facts." - Pending

12

The CMO "At Issue" Stall (Feb 6, 2026)

Alleged Bad Faith Delay Tactics - Defense Counsel refusing to draft the Case Management Order or engage in discovery by strictly interpreting the "at issue" timeline. Plaintiff alleges this is a calculated stall tactic designed specifically to avoid answering the forensic Requests for Admission (RFAs) regarding the 11:14 AM server logs. - (Pending Rule 16 Motion)

13

The "Redline" Gatekeeping (Feb 13, 2026)

Alleged Procedural Interference - Defense Counsel attempting to condition their C.R.C.P. 121 conferral on a demand that Plaintiff perform their paralegal work by providing a "redlined" document. Plaintiff argues this was an intentional gatekeeping tactic to miss the conferral deadline. - (Pending Judicial Review in JDF 622)

Remember: While we think the metadata from the Google time stamps and the cell carrier text message EXIF data is conclusive and should be considered evidence, we must keep in mind that these are all Allegations until a Judge deems them as Facts. - Pending

The Pattern of Practice

Pattern of Practice & Administrative Perjury:

"The Plaintiff alleges a documented Pattern of Bad Faith involving three distinct instances of administrative fraud presented to the State of Colorado. This pattern began in May 2024 with the original 'Triple Fraud' (Account #2), continued in November 2024 with the '48-Hour Sham' response (Account #5) where HR explicitly ignored forensic metadata, and culminated in August 2025 (Account #8) when the Defense recycled a known falsified report to sabotage government benefits. This repeated usage of fraudulent documentation—conducted after the General Manager was placed on formal legal notice—establishes Sustained Malice and a corporate culture that prioritizes the concealment of forensic facts over administrative truth.

Auditor’s Note on Pending Admissions: While the final responses to the Requests for Admission (RFAs) are pending, a 'Default' through silence is a logically anticipated course of action for the Defense. Should they choose not to answer, the Defense may seek to avoid the professional risk of perjury or the forfeiture of legal licensure. However, under C.R.C.P. 36, such a default constitutes a Conclusive Admission of Fact. This procedural election would not only solidify several of the accounts above but would also legally establish Management Collusion and Negligent Retention as admitted facts within the public record, clearing the path for Summary Judgment and a determination of exemplary damages.

AI as the Great Equalizer

This case represents a new frontier in litigation. Daniel utilized Artificial Intelligence as a high-speed analytical engine to process, categorize, and cross-reference hundreds of pages of discovery, cross-reference dates, and identify the metadata anomalies that formed the basis of his Complaint and Motions.

What began as a typical employment dispute has evolved into a case study on digital forensics. By stripping away the subjective testimony of coached witnesses and focusing entirely on the immutable data—the timestamps, the server logs, and the email chains—Daniel has leveled the playing field against one of the largest law firms in the world.

"The legal system is designed to be too complex for a layperson," Daniel concludes. "But data is the great equalizer. When you strip away the expensive motions and the legal jargon, you are left with a simple server log that says 11:14 AM. And no amount of billable hours can change the time on that clock."

The Attitude Adjustment

My objective in this litigation is not personal vindication, but Systemic Accountability. In the insurance and risk management industries, certain thresholds of loss trigger mandatory internal audits and board-level reviews. By bringing the Physical Facts of this case to light, I am ensuring that the necessary 'Risk Audit' occurs—forcing a level of institutional transparency that protects future employees, stakeholders, and the community from the documented collusion found in this file.

NOTE TO READERS: The exhibits presented above represent only a fraction of the forensic data currently held in the discovery file. Additional server logs, metadata, and communications regarding the "Chain of Command" have been processed and are currently being reviewed for future publication as this litigation proceeds.

The Allegation of "Prior Practice"

The Plaintiff further alleges that the speed and efficiency with which four separate layers of management (Station, District, HR, and GM) involving five specific managers aligned their narratives suggests this may not be an isolated incident. The coordination was too rapid to be improvised.

Should this matter proceed to trial, the Plaintiff intends to use forensic discovery to audit historical personnel files for a "Pattern of Practice." specifically investigating if these managers have a history of terminating and then rehiring "preferred" employees (like the accuser) while systematically purging those who report their misconduct.

"They operated like they had a playbook. Future discovery will determine if they have used it before."

LEGAL DISCLAIMER: This report details the allegations and forensic evidence presented in the active litigation of Daniel v. Envirotest Systems Corp (Case No. 2025CV243, District Court, Larimer County, CO). All statements regarding the conduct of the Defendant and its employees are allegations based on sworn affidavits, forensic server logs, and court filings currently pending before the Court. While the Plaintiff believes the forensic evidence is conclusive, a final judgment on the merits has not yet been issued. This report is published in the public interest to highlight issues regarding digital forensics in employment litigation.

Chris Daniel

I am a Claims Adjuster and Network Admin focused on Strategy & Systems Analysis. Basically, I investigate everything until I figure it out. From IT networks and insurance policies to stock market momentum, social media algorithms, and litigation tactics—I treat every challenge like a crime scene to be solved. (And no, it's not always Colonel Mustard with the Candlestick in the Living Room)

About page.

Food For Thought

"The fears you don’t face become your limitations."

- Robin Sharma

All Rights Reserved.